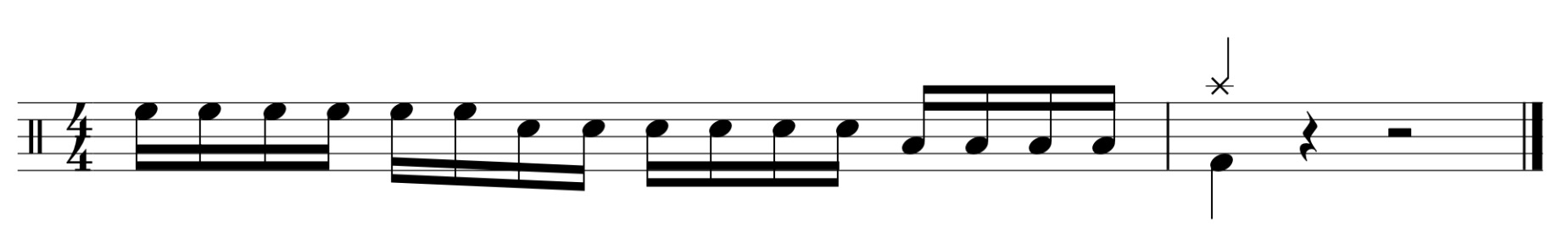

Joshua Redman and Christian McBride play this ending on the tune “On The Sunny Side Of The Street” from Redman’s self-titled 1993 debut album.

Bars 1 and 2 have clear elements of the common bebop language:

- syncopated rhythm with a pickup beat

- eighth note lines that outline the harmony

- chromatic passing tones and enclosures that lead to harmonic tones on strong beats

The second half (starting with the C on bar 3) quotes the classic Strayhorn/Ellington ending on “Take The “A” Train” (originally recorded in 1941)

The final bit of vocabulary (beat 3 on bar 4) I first heard on the tune “Four” from Miles Davis’ Blue Haze (1954). I don’t know for sure whether that is the earliest recorded use of the phrase, but I’ve heard it used often. I particularly like the surprise harmonic substitution by the bass moving down a tritone from C to F#.

Listening

- Joshua Redman, “On The Sunny Side Of The Street,” Joshua Redman, 1993

- Duke Ellington and his Orchestra, “Take The “A” Train,” Never No Lament: The Blanton-Webster Band, 1941

- Miles Davis, “Four,” Blue Haze, 1954