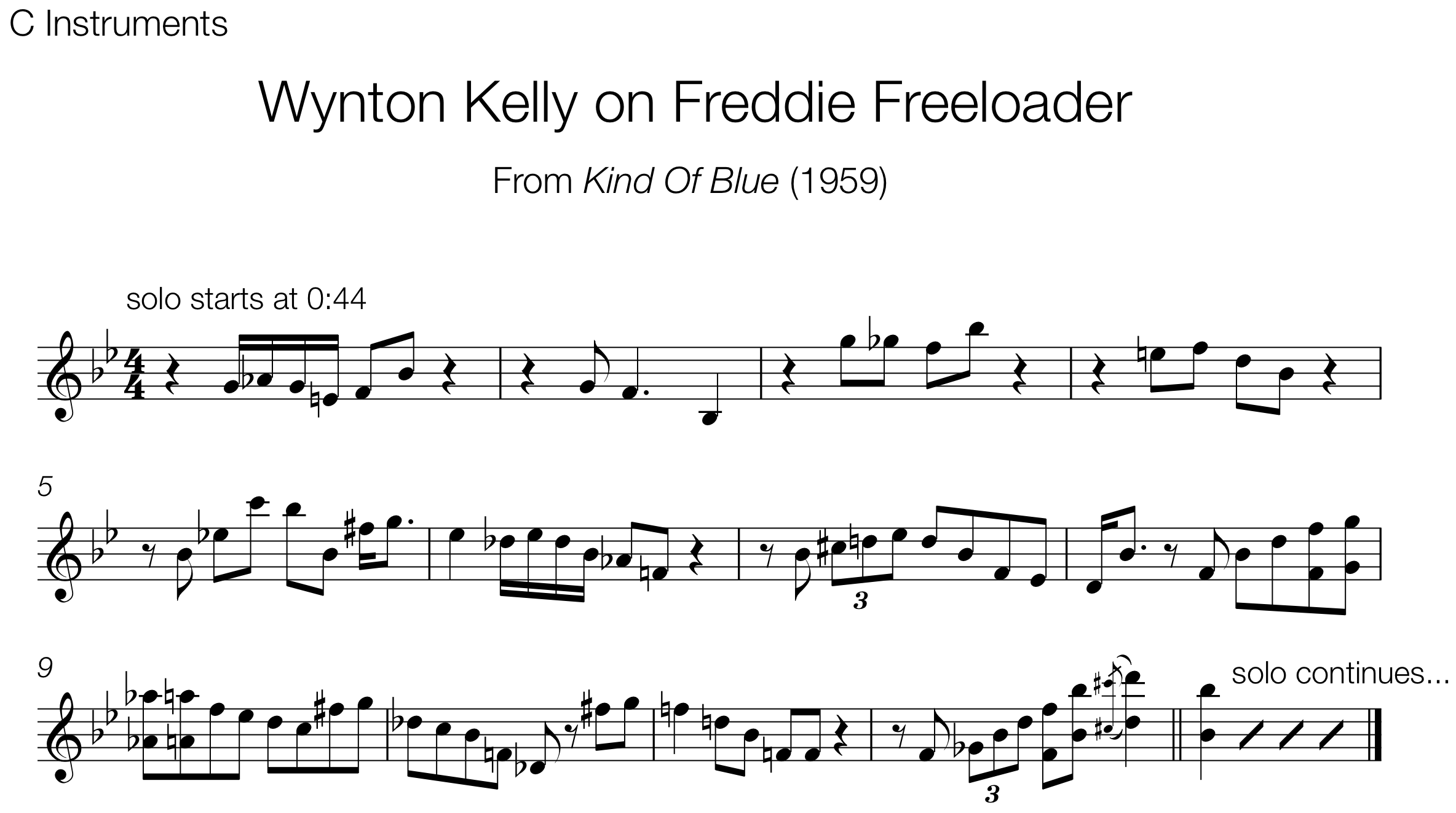

This weekend I’ll be playing in the house band for an educational jam session. It’s always a pleasure to work with students as they muster up the courage to improvise on a tune, or confidently showcase the techniques they’ve been working on.

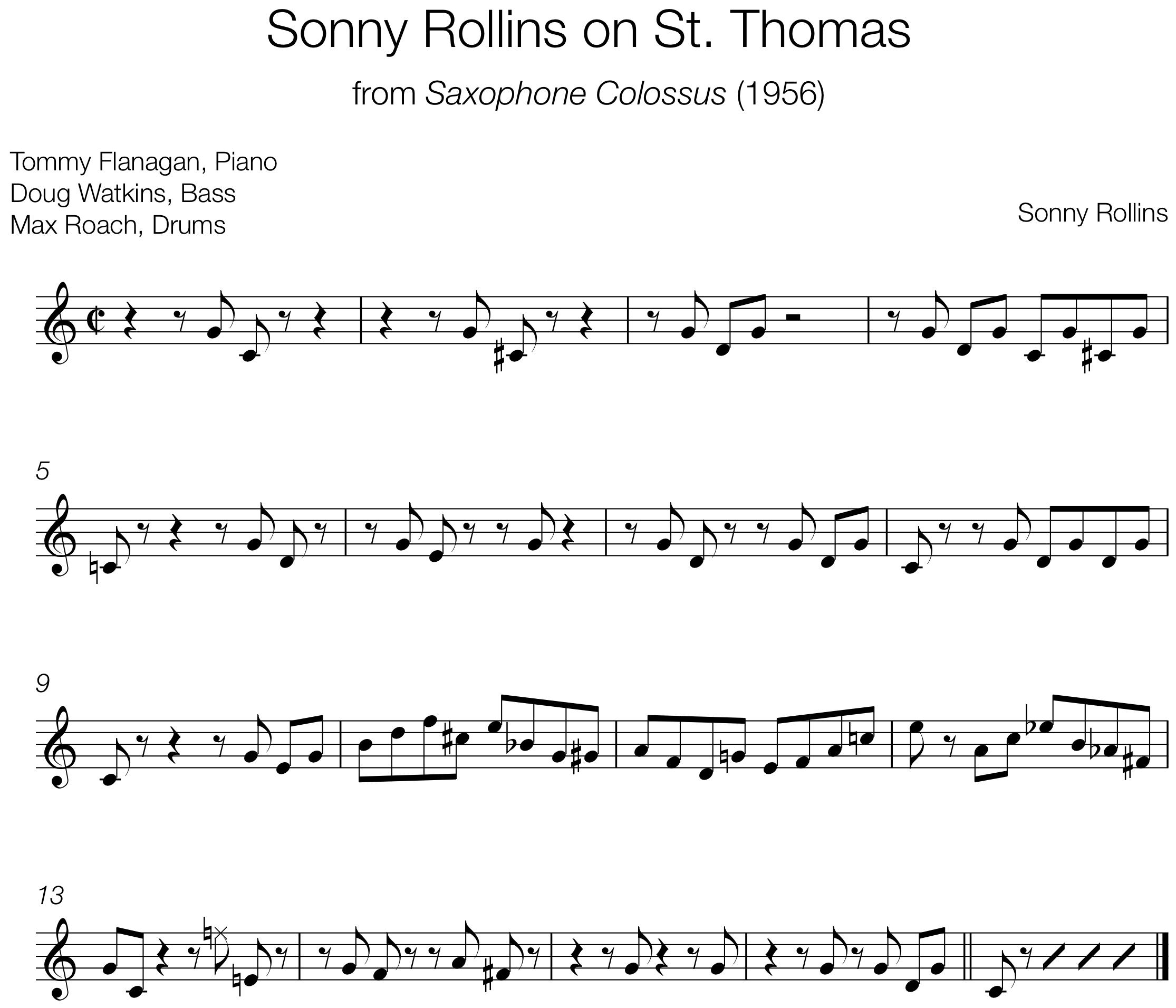

One of our jam tunes this week will be Doxy, written by Sonny Rollins. This tune became an early jazz standard and is often one of the first tunes that beginning improvisers learn.

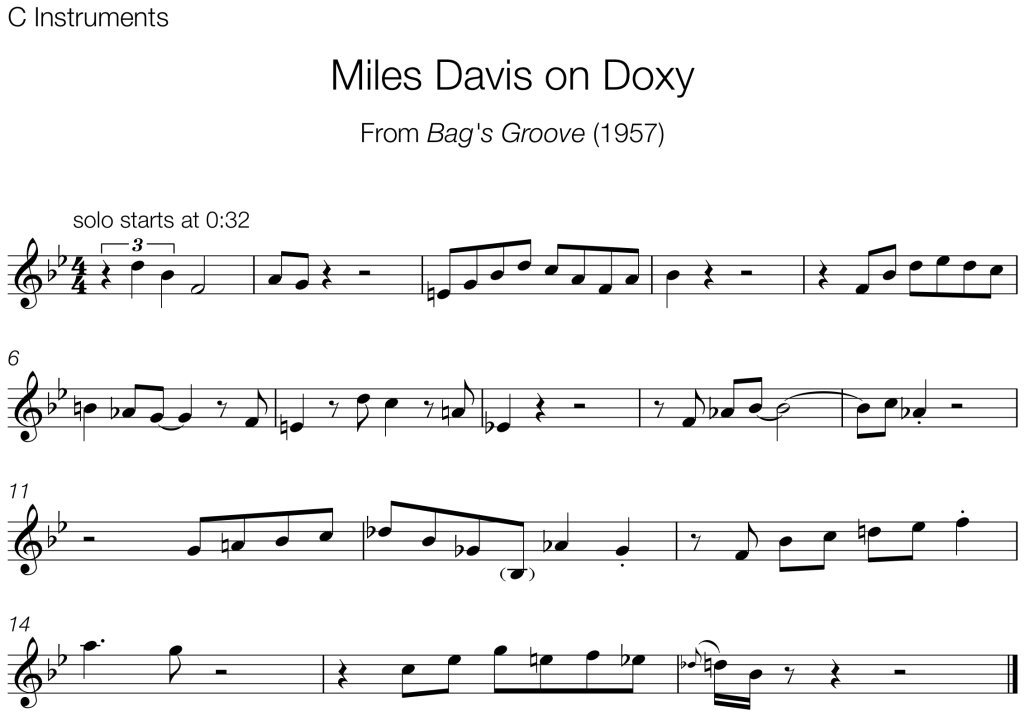

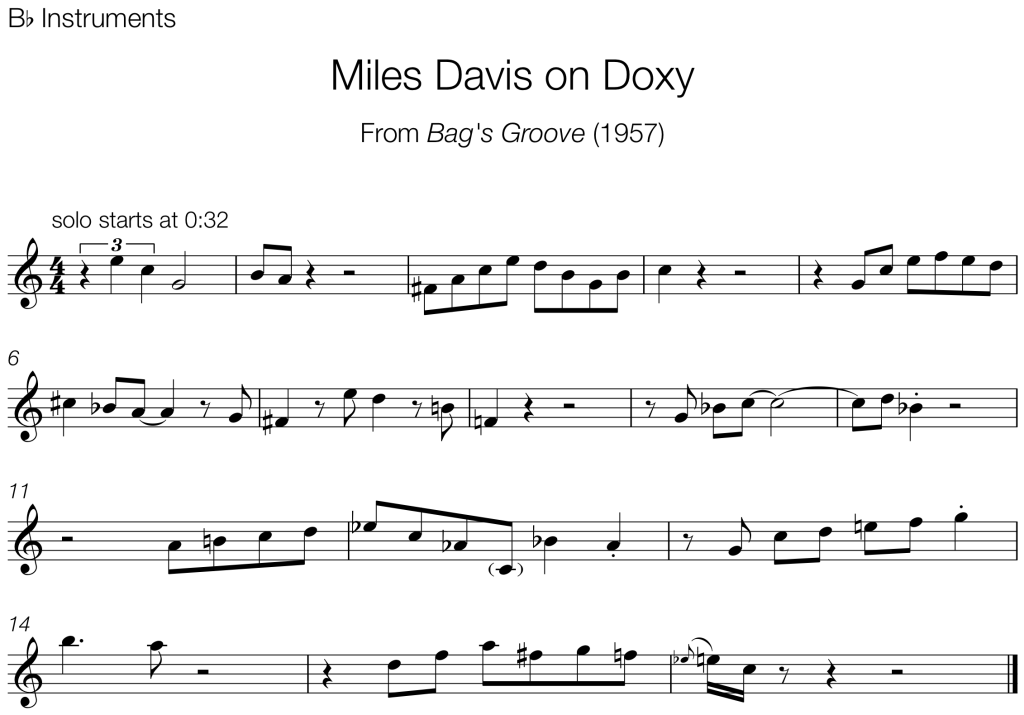

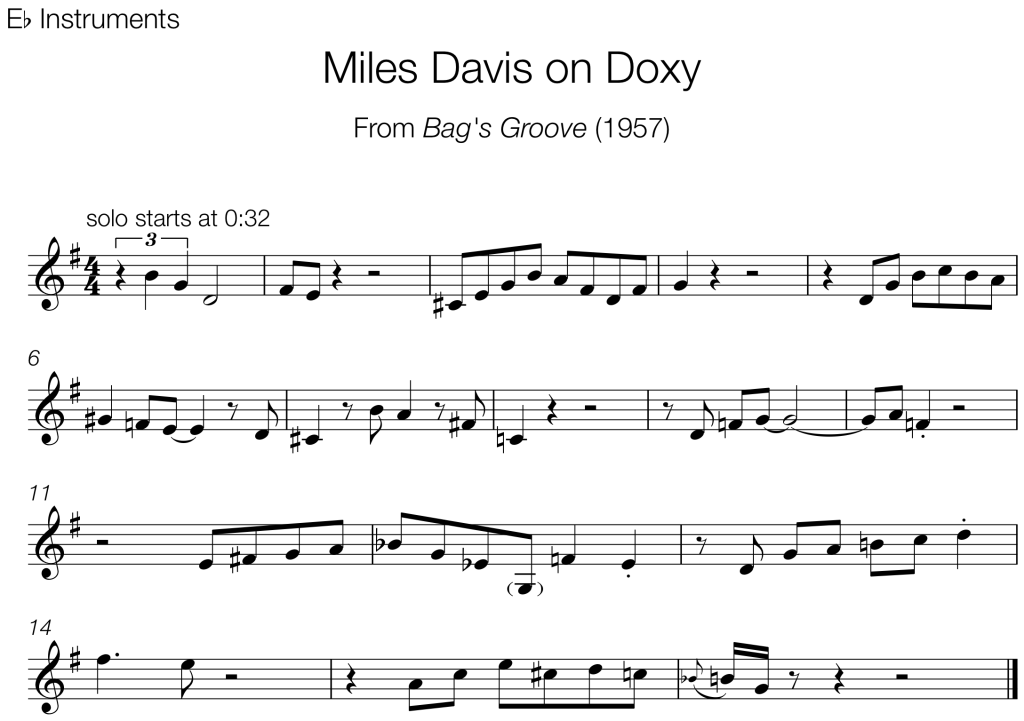

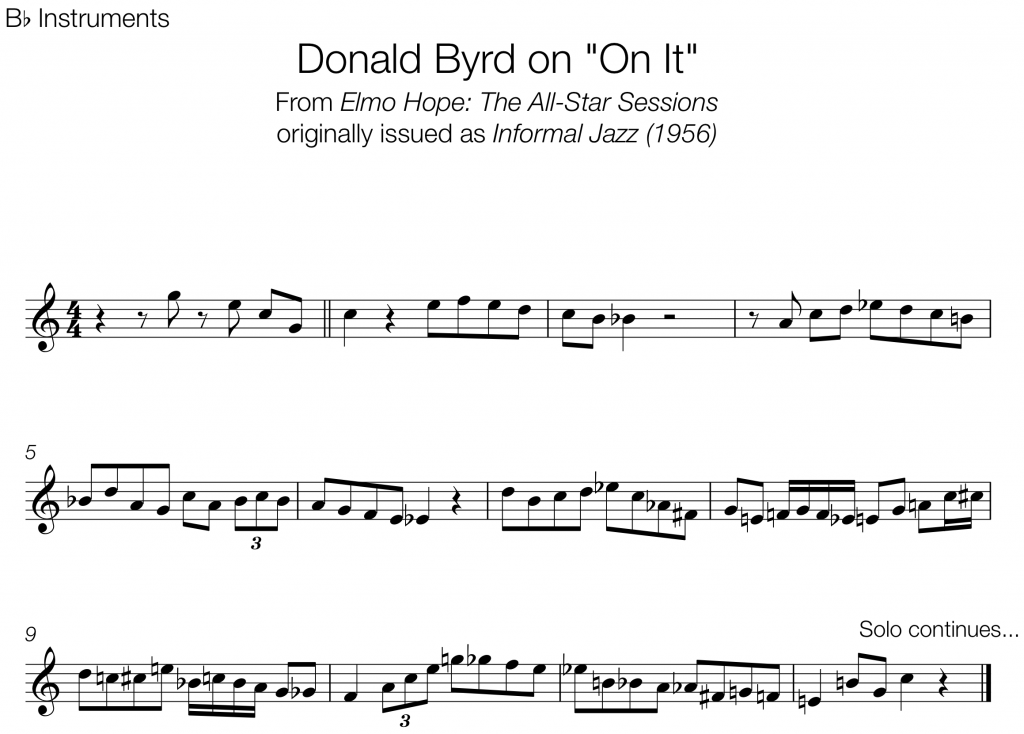

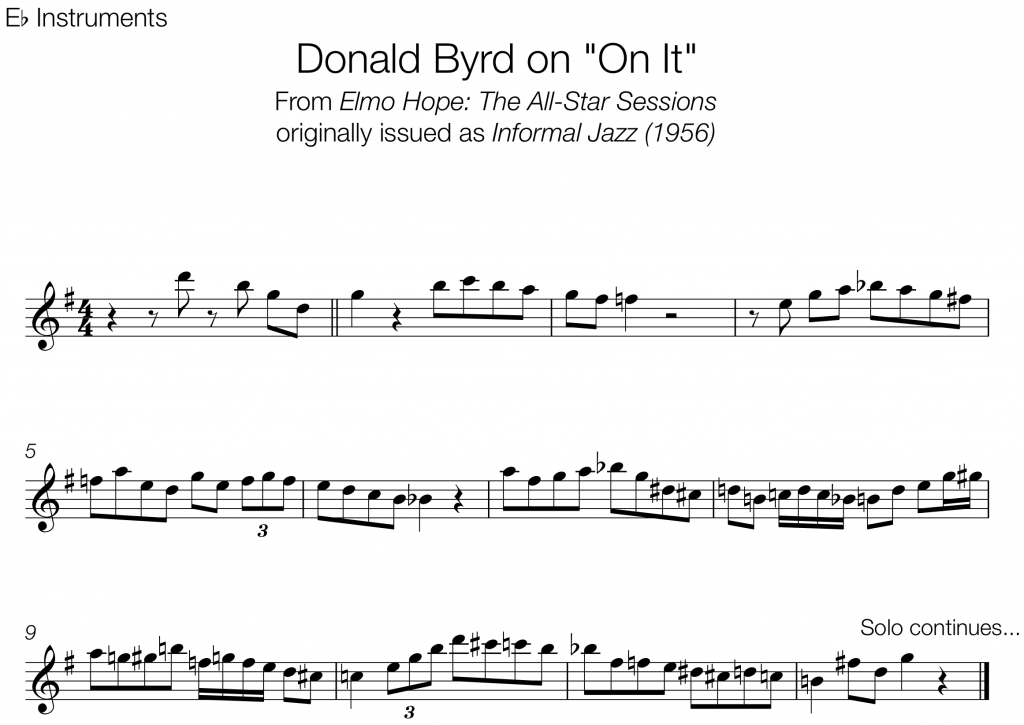

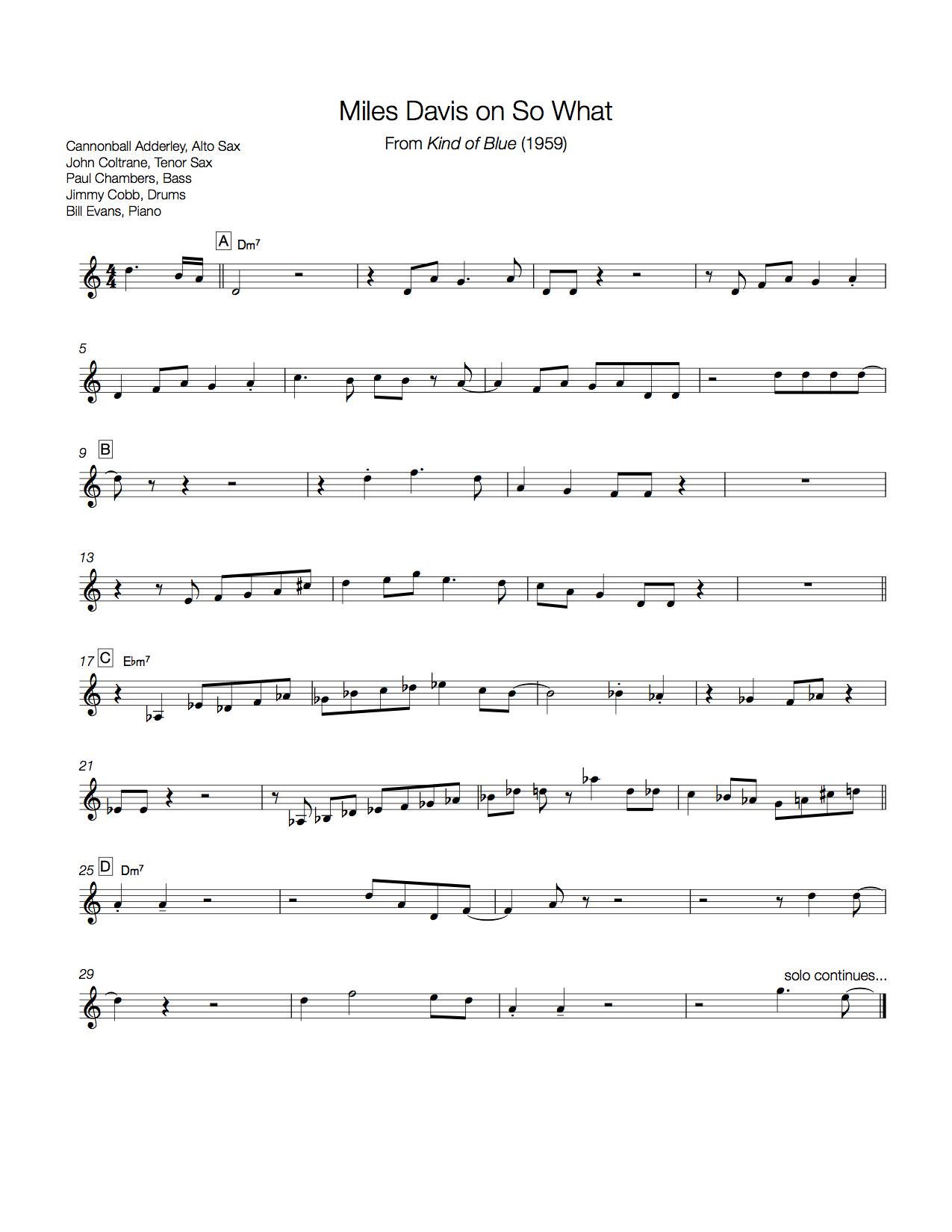

For this week’s Transcription Tuesday, we’ll look at the beginning of Miles Davis’ solo on Doxy from the album Bag’s Groove released in 1957 (the actual recording took place three years earlier in 1954 and features Sonny Rollins on tenor saxophone, Horace Silver on piano, Percy Heath on bass, and Kenny Clarke on drums).

If you are new to the jazz language, this is a great solo to learn and to study. You can use the steps outlined in yesterday’s How To Start Transcribing to learn the solo by ear, and then check your work against the notated version below.

Once you’ve learned the sound of the solo, try to make sense of the note choices and rhythms by studying the harmony. I didn’t include the chord changes in the transcription, but careful listening to the bass and piano on the recording will reveal the harmony (or you can surely find a chord chart online).

I find the simplicity and clarity of this excerpt inspiring and the tune overall is fun to play. I encourage you to try using some of this language in your own playing.